Money Matters: Sales Versus Expenses: Growth or Profit

By Dr. Albert D. Bates

One of the never-ending challenges in improving profitability is that there is a great deal of uncertainty within many firms as to what sorts of actions should receive the most attention. This uncertainty is seen most clearly in trying to determine the relative importance of sales growth versus expense management.

The sales versus expense issue is exacerbated by the fact that sales growth has great public relations while expense control has the world’s worst PR. For most managers, sales growth is what is right and good, while expense control is considered inherently evil, at least until sales start to fall.

This report attempts to provide a non-emotional perspective regarding the degree to which sales growth and expense control should be emphasized in the firm. It will do so by examining how sales and expense control impact profit and then exploring ways to integrate sales and expenses.

The Profit Impact of Sales and Expenses

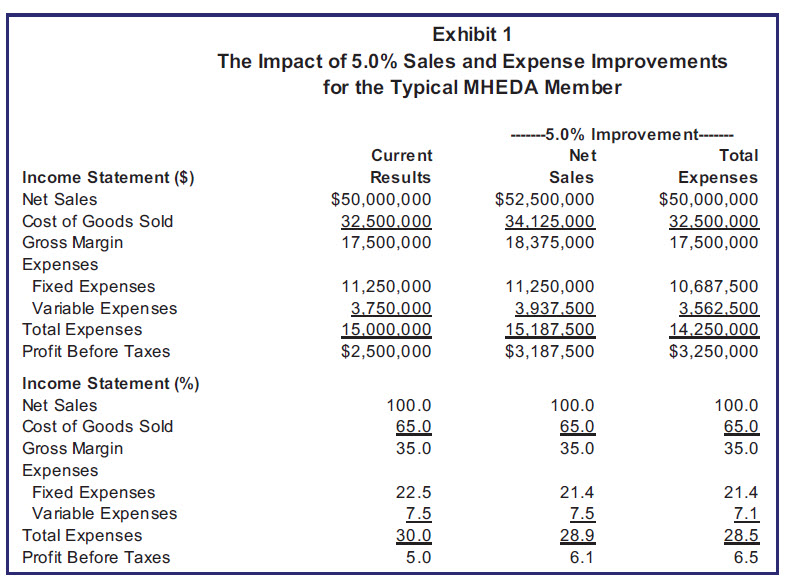

The first step in reconciling sales and expenses is to look dispassionately at the impact of each of these factors on bottom line results. Exhibit 1 does this for the typical MHEDA distributor, over the last five years, based upon the latest DSC Report. It is important to note from the outset that the exhibit examines how profits might have been different this year under alternative scenarios.

As can be seen in the first column of numbers, the typical firm generates $50 million in sales, operates on a gross margin of 35% of sales and produces a bottom-line profit of 5% of sales or $2,550,000.

As can be seen in the first column of numbers, the typical firm generates $50 million in sales, operates on a gross margin of 35% of sales and produces a bottom-line profit of 5% of sales or $2,550,000.

In any profit analysis, it is important to break expenses out into their fixed and variable components. Fixed expenses are overhead expenses that will not change during this year unless the firm takes a specific action to change them. For example, hiring an additional office employee would increase the firm’s fixed expenses.

Variable expenses are those that will change automatically along with sales during the year. Items such as sales commissions and bad debts fall into this category.

They tend to be a relatively consistent percentage of sales.

Fixed expenses for this typical MHEDA member are assumed to be $11,250,000 while variable expenses are 7.5% of sales. These are, of course, estimates. They represent a serviceable approximation for all MHEDA members. None of the conclusions of the analysis will be changed if the estimates are off a little.

The last two columns of numbers look at the profit implications of either increasing sales or decreasing total expenses. In both instances, the improvement factor is 5%. That is, sales are increased by 5% or expenses are decreased by the same 5%.

With a 5% sales increase, the first three lines on the income statement — sales, cost of goods sold and gross margin — all increase by 5%. Since the analysis focuses on this year, the fixed expenses remain the same. Variable expenses increase along with sales and continue to be 7.5% of the sales volume. The impact is a profit improvement of 27.5%, from $2,500,000 to $3,187,500.

In the last column of numbers net sales, cost of goods sold and gross margin remain constant. Instead of a sales increase, total expenses are reduced by 5%. Note that total expenses are reduced, including both fixed and variable. This means that no line items are sacrosanct, including commission rates paid.

As can be seen, an expense reduction of 5% drives profit up slightly more than a sales increase of the same magnitude. Specifically, profit increases from the $2,500,000 figure to $3,250,000, an increase of 30%.

This set of economics represents a truism for managers in all situations. Expense cuts will always produce greater increases in profits than sales increases of the same magnitude. Always is a fairly strong word. The hard-cold profit analysis says nothing about the ease of making the changes or management’s enthusiasm for doing so. Still, more is more.

Integrating Sales and Expenses

To reiterate, expense control will always have a bigger “bang for the buck” than increasing sales. At the same time, sales growth will always warm the cockles of a manager’s heart much more than expense control. The challenge is to find approaches that balance both sides of the impact versus enthusiasm argument. Two such approaches are especially important.

Positioning Productivity Properly

For a lot of managers, productivity is the silver bullet for controlling costs. The idea is to maintain sales growth and allow new technology to deal with the cost issues. This is a dangerous perspective.

Indeed, every firm also must stay on top of new technology to enhance productivity. However, every firm also must be aware that in the long term, such enhancements will not solve the expense challenges and may not even diminish them significantly.

To use professorial language, technology is a necessary — but not sufficient — vehicle for controlling costs. Every firm that fails to stay on top of technology will be at an expense disadvantage vis-à-vis its competition. However, such an investment will only allow the firm to maintain cost parity versus the competition. The motto should be to invest steadily but continue to look beyond new technology.

Re-thinking the Customer Set

All customers are not created equally. Some are wonderful to work with, some are terrible. From an economic perspective, only a small subset of customers are truly profitable for the distributor. It is essential to focus on customer profitability as a management responsibility.

Moving Forward

Distributors must balance sales and expenses. The traditional either-or thinking must be modified to reflect the opportunities to increase sales and control expenses simultaneously. The profit implications of such actions are substantial. Alas, achieving the profit potential requires new thinking by management.

About the Author

Dr. Albert D. Bates is the Principal of the Distribution Performance Project. His latest book, “Breaking Down the Profit Barriers in Distribution” is suggested reading for middle managers.

©2024 DPP. MHEDA has unlimited duplication rights for this manuscript. Further, members may duplicate this report for their internal use in any way desired. Duplication by any other organization in any manner is strictly prohibited.