Today’s leaders must develop a resilient mindset to improve performance in a fast-paced world.

Today’s leaders must develop a resilient mindset to improve performance in a fast-paced world.

By Elsbeth Russell

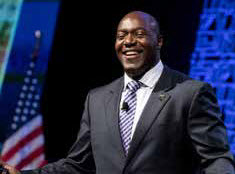

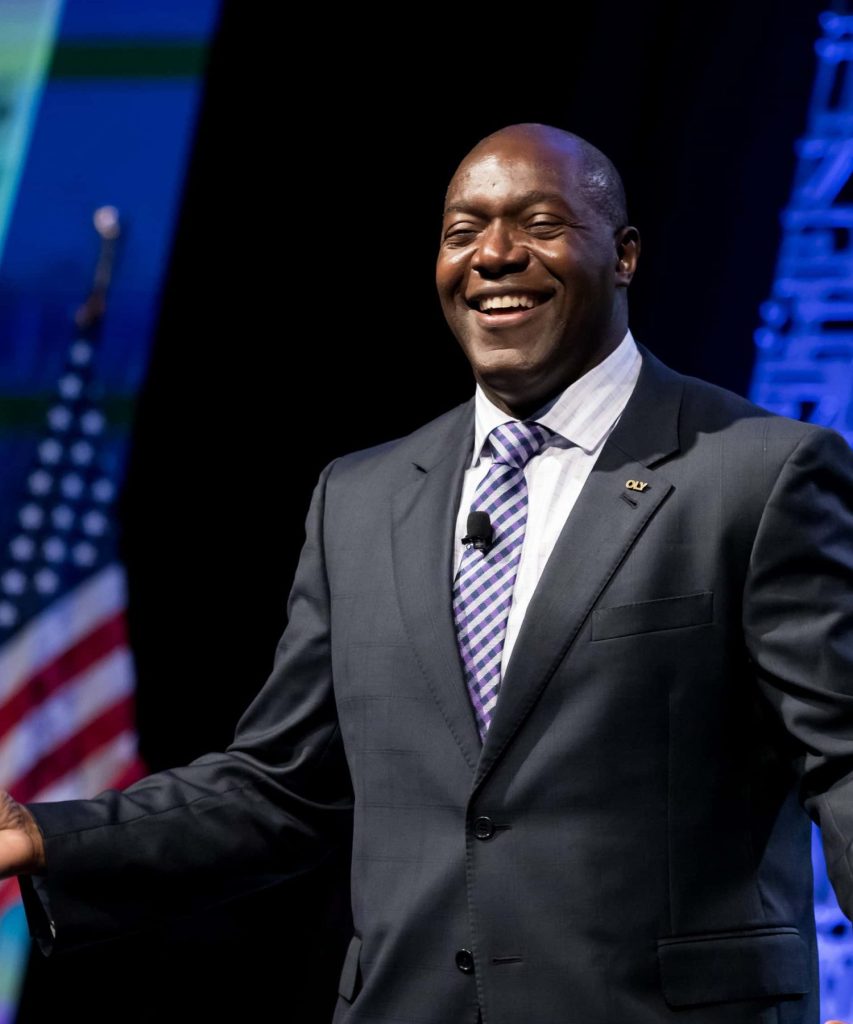

As a three-time Olympian with Jamaica’s original bobsled team, Devon Harris did not start out with aspirations to become a professional athlete. Instead, Harris had a goal of being a military officer in the Army.

These two pathways proved to have one important thing in common, though – they both required a mindset of achievement and resilience that Harris says is key for young leaders to develop.

Harris, a speaker at the 2022 Emerging Leaders Conference, sat down with the MHEDA Journal to share a bit about his background, philosophy of goal setting for up-and-coming leaders and how he’s feeling about the new generation.

MHEDA Journal: How did you get your start on the Jamaican Bobsled Team? Was that a goal of yours or an unexpected opportunity?

Harris: I grew up in a rough neighborhood in Kingston, a place called Olympic Gardens, which sounds like a fitting place for a future Olympian to have been brought up in. But, yeah, it was tough and gritty. I think in today’s world, when people see someone like me who is noted for sport, coming from a background like that, the assumption is that, ‘Oh, I’ve always seen sports as my way out,’ but it was not.

I wanted to be a soldier and that was influenced by stories from my grandmother, who I spent my early years with. She’d tell me these amazing stories that kind of stuck with me and impressed upon me – inspired me to want to be a soldier, first of all – but impressed upon me this idea that you could go after goals that were seemingly impossible or difficult.

So, as I grew older I realized I could actually become an officer in the army. I saw that as the quickest way out of the ghetto combined with the fact that I genuinely wanted to be in the army. So that was my way.

The Olympics thing started when I was about 15. I started running track and training seriously, and in 1979, a year before the Moscow Olympic games, ABC’s ‘Wide World of Sports’ had a series called ‘Road to Moscow.’ In it, they highlighted athletes from around the world, telling their stories – sporting stories and life stories outside of sports. When you think of Olympic athletes, you think of these super-human beings. What stood out in my mind from that series was how average and ordinary they were – but they had this extraordinary dream and an equally strong desire to make those dreams come true.

So, when you couple that with this kind of mindset that I developed from those stories that my grandmother told me it was like, ‘Oh my God, I think I could become an Olympian as well.’ So if you fast forward, I’m 21 years old, I’m a newly minted Army officer. I remember walking one day and having this intense conversation with myself: ‘You have to achieve your big dreams. What are you gonna do with the rest of your life?’ (Which I kind of smile at now because I don’t know how many 21-year-olds have those kinds of conversations, but anyway…) I’m like, ‘Oh yeah, the Olympics.’ It was ‘87 and the Olympics were coming up in 1988 in Seoul, Korea. The winter Olympics were never on the radar.

So now I’m running five miles a day trying to get fit. I was a middle distance runner – I ran 800 and 1500 meters. So I did the only thing I knew how to do and just went to go run. So I would go do these runs hoping that maybe I could get fit. I had no other plan about how I was going to get to the Olympic games.

Then right about that time, two Americans who lived in Jamaica came up with the idea to start the team. They weren’t able to get guys on the summer team to do it so they came to the Army, looking for athletes. My Colonel discovered me. I ran this race and they were like, ‘Oh my God, he’s fit!’ So my Colonel told me to go to the team trials.

Honestly, not so much because he thought I was this amazing athlete. You know, the fact that I ran well in that cross-country race obviously caught his eye, but there was a philosophy in the Army that said officers must always participate and he had a bunch of enlisted men going. So he thought he’d send this young fit officer to the team trials as well, to make up numbers.

By the way, when I first heard that Jamaica was gonna have a bobsled team, I thought it was a ridiculous idea and I remember saying nobody could ever get me to go on one of those things.

You know, although I could not describe a bobsled to you, all I knew was it was a winter sport first, and that it was dangerous. But now the Colonel told me to go to the team trials, and my mindset shifted from, ‘I would never do that,’ to ‘Oh my God, I have to make this team. How am I gonna make it?’ I had no clue because I didn’t think I was – I was what I would describe as ‘army fit.’ You know, I could walk 100 miles with 50 pounds on my back and a rifle in my hand.

I didn’t think I was sports fit. I hadn’t done any intense sports training for almost two years because of joining the army. But anyway, I went to the team trials and I tried my hardest. I think they liked my smile. That’s probably why they selected me. No, I just tried hard. I really tried hard.

There was one test that was called a push test – it’s a push test with a make-shift sled on wheels. And although I didn’t know anything about bobsledding I just intuitively knew that this had to be the most important test out of all of the others. I ended up with the two fastest pushes – faster than even the fastest sprinter. So I guess that, coupled with that smile, they go, ‘Yeah, he has to be on the team.’ So that’s how I ended up on the team. The short story, the short version.

MJ: What has life been like since becoming a three-time Olympian? How did that experience shape your trajectory in life?

DH: The army was my primary focus. The idea of going to the Olympics was – I’ve started to describe it as my side hustle. It wasn’t the thing that I felt was gonna get me out of the ghettos. Being an army officer was.

But then I became an Olympian and that definitely changed the trajectory of my life. Not just the fact that I was an Olympian but everything that goes along with it. The obstacles and, most importantly, the mindset and the exposure that I got from it. So when I was standing there in Olympic Gardens kind of looking out and dreaming, you know, ‘Man, if I could become an Army officer… My God, I could not ask for more.’ And then I became an Army officer and then I became an Olympian and I started to travel a little bit more and I started to see other things in the world that I could never have imagined seeing from my vantage point in the hood. And I’m like, ‘Oh, so all of this is all there too. I did not know.’ So it went from ‘My God. If I could just do that, I couldn’t ask for more’ to like, ‘Well, this is cool, you know, I want some of that.’ So one thing led to another and here we are.

MJ: What was it like to become a teammate and leader in your 20s?

DH: I was in training at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst and the motto there is ‘Serve to lead.’ … As I matched up the steps to officially become an officer the motto ‘Serve to lead’ just hit me at that moment.

Everything that I’m gonna do from this point on is not going to be training anymore. There’s not gonna be an instructor there giving me quick feedback and it’s real. I think leading to that moment, I really wondered how am I going to do this, right? I’m 12 days shy of my 21st birthday, and I’m gonna be leading men who, many of them were in the Army before me and are older than I am. I thought, ‘Oh, well, you know, I’m better trained than them.’ And by that, I mean, I did the training in Jamaica and then I’d just done this stuff in England. I’m like, ‘Whoa, this is so much better. So, so far superior.’ So that’s a thing that I held onto anyway, that gave me the confidence that, ‘You know, what? I actually do know a little bit more than they do. I’m better trained.’ And then you know, it’s just like, how do you learn to swim? You kinda have to jump in the water.

I kind of grew into it and, you know, being on the bobsled team, when I think of leadership there’s something I speak about these days: personal leadership first before you can actually lead others.

I think back on my life, and I think I demonstrated a high level of personal leadership. Taking responsibility and wanting to grow and learn and do your best and be your best. And I think that kind of mindset also helped me in terms of trying to lead my soldiers because of the way I thought. And being on the bobsled team… Well, what were the things I could control? You know, how much I could learn about the sport and how hard I could work, how much effort I could put in during the workouts and so on and so forth.

But yeah, it was an alien world. Not just bobsledding, but everything that came with it. Like I’d been sitting at a table and they were talking about corporate sponsorships and all of that language sounded so freaking foreign to me. But you know, my ears are wide open. I’m just listening because I can’t add anything to the conversation. I deferred a lot and just asked questions and now I can actually use those words in a sentence.

MJ: It can be difficult for many young people to navigate the beginning of their careers in today’s environment – the pandemic, remote work, and an unprecedented job landscape. How can people, especially those early in their careers, navigate these challenges and make the most of today’s work environment?

DH: It is indeed a strange new world. But it’s a strange new world for everyone. It’s not just them. Granted you might be starting out. I read something a long time ago: A truly great person is the one who finds a way to surmount their particular challenges.

So you can go, ‘Well, it was easy for you, you know, everybody was in the office every day.’ Yeah. But that brings its own unique set of challenges as well, right? So I think success principles are universal now.

You just apply them to different scenarios. You still need to open your ears and listen and ask questions. People definitely have an advantage that I wouldn’t have had back then. It’s called the internet. There’s so much more information out there that I could not have had access to as I was starting my journey. It’s just so much easier to connect and to reach out to people as well, to ask those questions.

So even if you’re not sitting at a table having a meal and listening to these conversations, you can hear a word, ‘Oh, conference sponsorship? Google, what does that mean?’ So it comes back down to, again, personal leadership. It’s not fun at the moment, but in the long run you’ll reap the benefits for sure.

MJ: Your book is called Goals: How to Set and Achieve Them. What would you say is the biggest mistake that leaders make when it comes to goalsetting?

DH: It’s probably perfection. And I’m speaking as a reformed perfectionist. From my own experience, it is one of the greatest motivators out there. Man, this thing will get you to work hard, right? Cause you want it, right? And you’ll go to any length and do everything to get it. But what I realized is that you can never be truly perfect.

The challenge with the perfectionist mentality is that it’ll still not be enough. I often say in my speeches, you could move a mountain and perfection will go, ‘Well, it wasn’t tall enough. You didn’t move it far enough.’ Excellence might say you are not good enough at this moment, but that was everything you had. Right? And so at the end of the night, when you put your head on the pillow, if you know, in your heart that, in that moment, that was everything you had, you can live to fight another day.

MJ: Do you feel like there are specific opportunities – or on the flip side, challenges – that young people specifically have when they’re on a leadership path?

DH: You know, perhaps the whole idea of diversity, equity and inclusion. We’re just living in a world that’s very different from the one I lived in and things tend to be more binary. Then it was like – forgive the pun – black or white, and now you have all these different shades as it relates to all the social connections and interconnections.

That obviously spills over into the business world as well, right? Because people tend to want to separate business from how we live as a society, which does not necessarily work because it’s human beings occupying both spaces.

And that’s going to be the biggest opportunity and biggest challenge in my opinion. Just finding a way to create space for everyone.

About the Author

Elsbeth W. Russell is an award-winning writer with a passion for helping build communities of all types.